- Home

- Brad Schaeffer

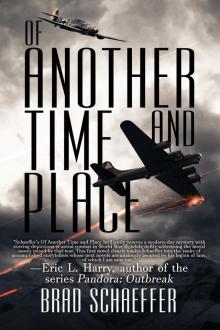

Of Another Time and Place Page 8

Of Another Time and Place Read online

Page 8

“This is cozy,” he said, swallowing hard.

I stood up and tried to put on an innocent front. “Johann. It got too noisy out there.” But then Amelia rested her palm on my shoulder and sat me back down. Her hand was shaking.

Keitel’s expression remained fixed. “You best get up, Becker. I don’t think I like you so close to my bride.” I remained seated.

Amelia then spoke: “I’m not your bride yet, Johann Keitel. And I do not appreciate you following me as your SS friends do Gypsies and Jews.”

“Then don’t associate with them,” he responded without a beat. His black eyes flitted to me, then back to her. “Or their friends.”

He was referring to Krup. A chill ran through me. I knew my fraternization was calling attention to me…and my family. I suddenly felt the need to explain my association with a Jew to this soon-to-be SS man with the most powerful family in town. “Is there anyone else in Stauffenberg who can teach me to play?” I asked him.

“I don’t have time to learn such frivolous parlor tricks.”

“Oh yes,” Amelia sneered. “That’s right, Johann. You’re going to be a big man in the Nazi party. I forgot. Maybe when you’re done breaking more defenseless shopkeeper’s windows, you can shove your nose far enough into Heydrich’s crotch. I hear he likes boys like you.”

Keitel’s body went rigid as if touched by a live wire. His eyes narrowed to hyphens and his fists clenched. He suddenly looked foolish in his Hitler Youth garb. Like a patsy. But he soon set this brash woman straight: “I could have you arrested right now for saying such a thing. You too, Becker. You better be very careful what you say next…Fräulein Amelia.” He was reaching for his whistle that hung around his long neck.

“You’d have your own fiancée arrested?” I asked in astonishment.

“Watch me,” he said with a coldness in his voice that told me he was serious. Who is this? I thought. Where’s the boy I was just drinking with in the grand hall?

“What the hell’s gotten into you, Johann?” I said, diffusing the situation and returning the subject to the more benign music. “Since when is music of German masters like Bach or Beethoven frivolous? Don’t I see you marching through the streets singing martial tunes?”

That disarmed him. He was still just a boy like me, despite his haughty bravado. “That’s not what I meant. I love all things German. And the New Germany will not have the patience for vermin like your piano instructor. Or with that one, if she’s not careful,” he said while aiming a finger at the defiant Amelia. The change in personality, as if I were confronted by his dark twin, was both unnerving and fascinating. Was he stable?

I condescended to chuckle at his little tirade, which just disarmed him more.

Amelia shook her head, as if she’d heard his cautions before. “What do you want, Johann?”

“To check on you,” he replied.

“You mean to check up on me.”

Keitel looked at me, then her, then me again. “No…but should I?”

I exhaled and rolled my eyes. “Come on, Johann. We’re just taking a break from the noise of the party.” I turned to Amelia, and her look betrayed to us both that I was lying. My heart was thumping. Then I did something foolish. The champagne was clouding my judgment, and I forgot who was standing before me. “Here, let me play a wedding march in your honor. It’s by Bach. Then you tell me what’s frivolous.”

He placed his hands behind his back, like a drill sergeant. “Very well, Becker. Maybe I’m being silly. Let me hear it.”

Amelia watched me quizzically. I played a wonderful march in C major that I’d recently adapted for piano. It was only three pages, but the melody was familiar. I could see by the end through the corner of my eye that even Keitel was able to crack a thin smile. Amelia, however, was sitting next to me and staring with a mixture of confusion and then the slowly broadening grin of one in on a joke. Which she was. But for the Hitlerite in our midst, I know she would have put her arms around me.

When I finished, I turned to Johann. “Well?” I said.

He smiled. “Bach. How could one not enjoy such music? It’s as the Führer says; the German way is the true way. With the arts as well. You’ve proven that point.”

I started laughing. “That was ‘The Wedding March,’ by Felix Mendelssohn.”

Amelia suddenly burst into boisterous laughter.

“What sort of nonsense is this?” demanded Keitel, his face turning deep crimson.

“You just praised the work of a Jew. One whose music our Führer has banned.” I sat there eyeing him in contemptuous silence.

Amelia was not so contained. “Watch out, Johann. Perhaps you should blow your little whistle on yourself?”

Keitel stammered, feeling every bit the fool I’d just revealed him to be.

“You’re a bastard, Becker!” he screamed. Then he turned his frenzied gaze upon Amelia. “And you, you slut, I won’t tolerate your flirtations! I can assure you of that!”

I was stunned at his acidic vehemence, which had me soon questioning whether mocking Johann Keitel to win the affections of Amelia Engel was such a good trade. Obviously, I’d crossed the line. And something inside the boy must have snapped.

But Amelia didn’t take kindly to his insult, and in one phrase sowed a seed of hatred this future SS officer would cultivate over the course of many years that would eventually bear tragic fruit.

“Slut?” she fired at him. “Why, you Nazi troll! I am no one’s whore…least of all yours!” And then she pointed her shaking finger squarely in my direction and laid waste to my relationship with Johann Keitel. “If anything I’ll be his bride!”

His face went from red to ashen, as if someone had pulled out a stopper in his throat. He opened his mouth to speak but nothing was forthcoming. As he turned on his heels and stormed away, Amelia leapt off the bench and walked briskly after him. She stopped at the opened doorway and shouted at his back as he marched down the hallway back towards the ballroom and his guests. “Do you want an encore, you small-minded boy?”

She slammed the doors violently and strode back with clenched fists to sit back down on the bench with a huff. She leaned against me, catching her breath. This woman was nobody’s handmaiden. I turned and whispered into her ear.

“You’re a remarkable woman, do you know that?”

Her anger fading, she looked at me with profound feelings and took my cheeks in both of her delicate hands. “And you’re a sweet boy.”

“This will be hard on Johann,” I said.

“I know,” she said dreamily, resting her head on my shoulder.

“And there’s a war coming.”

“I know.”

“I’ll have to do my duty.”

“I know.”

“You won’t have many friends tomorrow.”

“I know.”

As the festive intonations of Germany’s apogee continued just beyond the parlor doors, I took her chin under my forefinger and eased her lips onto mine. How often had I dreamt of this since I first felt her bosom press up against me as we took shelter under the malevolent shower of Nazi glass. Her lips, like sweet strawberries, took mine in kind and a shiver ran through me.

“I’ve wanted to do this for a long time,” I confessed.

“I know,” she said breathlessly. Her exhalations blew against my tingling ears. “I want you too.”

I pulled my head back. “Here?” I looked over to the door. “Is the door locked?” I asked as I ran my lips down the side of her swan-like neck and inhaled her feminine scent. My entire body felt as if it were being jolted with a mildly pleasant electric charge.

“I don’t care,” she cooed. “Let them see I’m free.”

She moaned and gasped as I slipped one hand up the folds of her dress to caress her bare thighs, while the other moved behind her and methodically began t

o undo the laces on the back of her dress one by one.

17

Stauffenberg lay dormant under a heavy quilt of thick, wet snow when word finally pushed its way through town that the much-anticipated wedding between Amelia Engel, the daughter of the widow Hanna, and Johann Keitel, son of George and Lila of the Keitelgesellschaft armaments fortune and Hitler Youth leader, had been cancelled. There was some local chatter about what—or who—was the cause of the rift, including speculation about the young prodigy Harmon Becker, who played pianoforte under the tutelage of the town’s remaining Jew. But the short-lived gossip storm soon subsided, buried like everything else under three feet of Bavarian powder.

Johann and I wouldn’t speak for five years. And when we did, the tone of our meeting was quite the opposite of our once cordial interactions. At the end of March 1939, the Keitels had their annual gala in celebration of Hitler’s assumption of power six years before. As was the custom of the richest family in town, every citizen of Stauffenberg received an invitation to ski and take in sleigh rides on their estate grounds. Everyone, that is, except for three families: the Krupinskis, the Engels, and the Beckers. And so it was made clear that SS man Johann Keitel counted me as an enemy…the equivalent of the Jewry he despised and the woman who had rejected him. I would have to be careful.

I spent the cold winter days with my time divided between my house and Amelia’s. There was talk of war commencing when the spring thaws ushered in Europe’s traditional campaigning season. To my father’s dismay, Paul’s zeal for the Nazi cause was growing as the local schoolmaster drummed into the children the purity of the Aryan race rather than the multiplication tables. I would often come into the house to find him crouched before the wireless, listening with his mouth wrenched into a satisfied smile and his eyes alit with the fire of patriotism while our Führer spoke to the youth of his nation:

“We do not want this nation to become soft,” his guttural, speechified voice exhorted the boys of my country. “Instead, it should be hard and you will have to harden yourselves while you are young. You must learn to accept deprivations without ever collapsing. Regardless of whatever we create and do, we shall pass away, but in you, Germany will live on and when nothing is left of us you will have to hold up the banner which some time ago we lifted out of nothingness [applause]. And I know it cannot be otherwise because you are flesh of our flesh, blood of our blood, and your young minds are filled with the same will that dominates us [applause]. You cannot be but united with us. And when the great columns of our movement march victoriously through Germany today I know that you will join these columns. And we know [wild applause] that Germany is before us, within us, and behind us.”

Time rolled on. Winter stubbornly surrendered to spring. The white cloak on the hillsides receded, revealing the patchworks of lime green that rolled away to blue mists under the watchful eye of the Alps to the southeast. Germany in 1939 was full of promise and excitement about the future. Amidst talk of imminent war, the people of Stauffenberg went about their daily routines. Anyone who paid attention to the Wochenschau newsreels offered at the local cinema could see that the Führer, through his mouthpiece Goebbels, was steeling the nation for a fight. But where would the first blow fall? And against whom? Those were the unanswered questions during those last fleeting hours before the lamps of Europe went out again. The second hand of destiny was ticking ever louder in our collective ears.

Summer brought clear skies and dry roads. One fine morning, I stood on the sidewalk and observed a battalion of young, as-yet-untested Landsers as they wound their way in two lines through the narrow streets. These were battle columns. Infantrymen with their summer green tunics and calf-hugging jackboots tramp-tramped on the cobbles through the Himmelplatz and out of town, passing under the Rathaus tower and then crossing the Main Bridge. They sang martial hymns to the Reich as they marched. The town’s women, in their colorful embroidered dirndls indigenous to the Oberfranken, lined the streets waving, cheering, and tossing bouquets at the smiling troops. It all looked so clean, so German. National pride swelled in me at the sight of these handsome, disciplined centurions of the Fatherland…regardless of what was happening to Krup and his family.

But I wasn’t blind to the realities of a foot soldier’s life. I could not see myself in their ranks as a human packhorse. A typical Wehrmacht infantryman carried thirty pounds of equipment slung over the shoulder. The leather harness would hold together pouches for sixty rifle rounds and a spade, gas mask, water bottle, breadbasket containing some bread and meat or sausage, small fat tin, and bayonet. The infantrymen were being toughened for a field campaign. I did not envy these dusty, weary men on the move, their Mauser rifles (another eight pounds) slung casually from one aching shoulder to the other to alternate the weight for comfort. Their bell-shaped steel helmets were not worn while marching but rather attached by the chinstrap to the harness equipment. The hands idly played with the helmet straps, revealing the tedium of a long march. Aluminum identity disks dangled on light chains about the necks. Pressed in halves, they could be snapped in two should the fellow die, one half going to the unit chaplain or to the administrative office, the other sent home. I wondered how many discs would be bisected before this impending war was over.

As I gazed at these young boys, many my age, I was reminded of my duty. That night at supper, I informed my family of my intention to join the Luftwaffe if they would have me. My father said nothing. My mother disappeared upstairs and wept. Paul begged to go with me. “Not yet,” I said to him with a pat on the head, and he scurried off.

It was just me and Father sitting across from one another. He stared into his buttermilk. “You are decided then?”

“Yes, Papa,” I said. “I have no choice anyway. I’m conscription age.”

He took a deep breath. “Damn that…Austrian corporal and his fascist brown wood ticks.”

I was shocked. It was the first time in my life I had ever heard him utter a political thought. “You can’t mean that,” I protested.

He just looked up at me. “You’re doing what you must, Son. I understand and respect that. Since it’s unavoidable, I’d rather see you up in the air anyway. A smart move, but you always were the smart one. Smarter than Paul.” He lowered his voice. “Little fool and his Hitler Youth goon squad. They’re taking him to a camp next week.”

“Why’d you let him join? I managed to escape service…thanks

to you.”

He hesitated a moment. “They came to the door. Keitel at their head. First time I’ve seen that cocksure hector since Christmas. He’s fully ensconced in the SS now. He informed me that all youths between the ages of twelve and seventeen were ‘asked’ to join. If I refused to allow it, then I would lose my position as constable.” He waved his hand. “Oh hell, the little Nazi pest wanted to join anyway. So what do I care, right?”

I looked at him. “Papa,” I said soothingly. “Everything will be okay.”

“Do you know what that Keitel said to me?” I shook my head no. “He said, ‘We may not have you, Herr Becker, or even Harmon. But Paul will be one of us. We have your youth. Your future. That’s all that matters now.’” He pounded his fist on the table, spilling the milk on the faded wood surface. Through clenched teeth he growled: “I’m losing my boys to the Nazis.”

“No you’re not,” I assured him, wiping the milk up with my sleeve. “You’re just lending them to the Fatherland for a spell. You must have more faith, Papa.”

He pulled out his rosary from his breast pocket and stared down at it, fingering the beads. “My faith is all I have left.”

Amelia and I spent the last of our carefree days sitting in the Himmelplatz or taking care of her mother, who’d suffered what appeared to be a series of mini-strokes and was now slightly disabled. Hanna Engel, diminutive and white-haired, took a liking to me. “So much more earthy than Johann,” she would say as we pushed her in a wheelchair under the ver

million light of the gloaming along the Wilkestrasse. “That boy frightened me, my dear. But Harmon here is a doll.”

“Mother, you’ll embarrass him!” Amelia would giggle, noting that I was indeed blushing.

“He may blush, but does he ever speak?” she would observe with a hearty laugh that belied her condition. I adored Hanna Engel. But she would pay dearly for loving me.

When we could get away alone, Amelia and I would spend lazy afternoons strolling along the banks of the sleepy Main under a blanket of sunshine. Even in the mountains it was often warm enough to remove my shirt and let the sun ink a golden bronze on my back and shoulders. Amelia, so much a creature of the hills, remained milky fair and freckled. She would pick edelweiss as we walked through flowered cloisters of the old Wurtzenberg monastery or took in twilight chamber music concerts in the park.

Having officially applied as an officer candidate, I was slated to report for my first physical at the end of August. “Why do you wish to fly, Harmon?” she asked me once as we sat on the river bank with our bare feet splashing in the water.

For the first time I admitted to her my fears.

“Although he never speaks of it to me, I’ve heard my father in the Brauhaus with his old comrades telling stories of the Great War. The gassings, the maiming, the blood, and the stench of feces, urine, and decaying flesh all about him. Shells constantly warbling overhead. So utterly helpless.” I pointed to the heavens. “Up there is none of that. Besides,” I offered on a lighter note, “I was never one for crowds.”

She took my hand and turned my head away from the water to face her. Her crystal eyes could hold me in a trance. “I don’t want you going off to war at all, Harmon.”

“I have no choice,” I said quietly, trying to beat away thoughts of what fate had in store for me. I drew from my school lessons to garner strength in my ingrained love of country. I admit even I was infected with the disease of National Socialism. Amelia was the only one my age I knew who seemed immune. So my speech fell on skeptical ears. “There are forces at work greater than the self. We are a united hail of bullets now. I’m tied to the fate of this country, and the Führer…as are you,” I said, echoing the thoughts of ninety million German patriots.

Of Another Time and Place

Of Another Time and Place